PORK -- OR THE DANGERS OF PORK-EATING EXPOSED

Pork-raising has come to be one of the great industries of this country; and since the supply is wholly regulated by the demand, it may be taken as a proper index of the prodigious quantities of swine�s flesh which are daily required to satisfy the gustatory demands of the American people. No other kind of animal food is so largely used as pork in its various forms of preparation. The Yankee makes his Sunday breakfast of pork and beans, while the same article is a prominent constituent of at least two meals each day during the remainder of the week. Pork and hominy is almost the sole element of the Texan farmer; while in the Western States pork and potatoes constitute the most substantial portion of the farmer�s bill of fare. The accompanying dish may be hominy, beans, or potatoes, but the main reliance is pork in each case.

In the case of no other animal is so large a portion of the dead carcass utilized as food. It seems to be considered that pork is such a delicacy that not a particle should be wasted. The fat and lean portions are eaten fresh, or carefully preserved by salting or smoking, or both. The tail is roasted; the snout, ears, and feet are pickled and eaten as souse; the intestine and lungs are eaten as tripe or made into sausages; black pudding is made of the blood; the liver, spleen, and kidneys are also prized; the pancreas and other glands are considered great delicacies; while even the skin is made into jelly. In fact, nothing is left of the beast, not even the bristles, which the shoemaker claims. Surely it must be quite an important matter, and one well deserving attention, if it can be shown that an animal which is thus literally devoured, and that in such immense quantities, is not only unfit for food, but one of the prime causes of many loathsome and painful maladies. Let us examine the hog a little, and see what can be determined respecting his real nature, and his office in the economy of nature, if he has any.

A Live Hog Examined

Look at that object in a filthy mud hole by the roadside. At first, you distinguish nothing but a pile of black, slimy mud. The dirty mass moves! You think of a reptile, a turtle, some uncouth monster, reveling his Stygian filth. A grunt! The mystery is solved. The sound betrays a hog. You avert your face and hasten by, sickened with disgust. Stop, friend, admire your savory ham, your souse, your tripe, your toothsome sausage in its native element. A dainty beast, isn�t he!

Gaze over into that sty, our pork-eating friend. Have you done so before? And would you prefer to be excused? Quite likely; but we will show you a dozen things you did not observe before. See the contented brute quietly reposing in the augmented filth of his own ordure! He seems to feel quite at home, doesn�t he? Look a little sharper, and scrutinize his skin. Is it smooth and healthy? Not exactly so. So obscured is it by tetter, and scurf, and mange, that you almost expect to see the rotten mass drop off as the grunting creature rubs it against any projecting corner which may furnish him a convenient scratching-place. As you glance around the pen, you observe that all such conveniences have been utilized until they are worn so smooth as to be almost inefficient.

Rouse the beast, and make him show his gait. See how he rolls along, a mountain of fat. If he were human, he would be advised to chew tobacco for his obesity, and would be expected to drop off any day of heart disease. And so he will do, unless the butcher forestalls nature by a few days. Indeed, not long ago a stout neighbor of his was quietly taking his breakfast from his trough, grunting his infinite satisfaction, when, without a moment�s warning or a single premonitory symptom, his heart ceased to beat, and he instantly expired without finishing his meal, much to the disappointment of his owner, who was anticipating the pleasure of quietly executing him a few hours later, and serving him up to his pork-loving patrons. Suppose his death had been delayed a few hours, or rather, suppose the butcher had got the start of nature a little, as he generally contrives to do!

But we have not yet finished the examination of our hog. If you can possibly prevail upon yourself to sacrifice your taste in the cause of science, pork-loving friend, just clamber over into the reeking sty, and take a nearer view of the animal that is destined to delight the palates of some of your friends, perhaps your own. Make him straighten out his fore legs. Now observe closely. Do you see the open sore or issue, a few inches above his foot on the inner side? Do you say it is a mere accidental abrasion? Find the same on the other leg; it is rather a wise and wonderful provision of nature. Grasp the leg high up and press downward. Now you see its utility, as a mass of corruption pours out. That opening is the outlet of a sewer. Yes, a scrofulous sewer; and hence the offensive, ichorous matter which discharges from it. Should you fill a syringe with mercury or some colored injecting fluid, and drive the contents into this same opening, you would be able to trace all through the body of the animal little pipes communicating with it.

What must be the condition of the body of an animal so foul as to require a regular system of drainage to convey away its teeming filth? Sometimes the outlet gets closed by the accumulation of external filth. Then the ichorous stream ceases to flow, and the animal quickly sickens and dies unless the owner cleanses the parts, and so opens anew the feculent fountain, and allows the festering poison to escape.

What dainty morsels those same feet and legs make! What a delicate flavor they have, as every epicure asserts! Do you suppose the corruption with which they are saturated has any influence upon their taste and healthfulness?

Perhaps you are thoroughly disgusted now, and would like to leave the scene. Pause a moment. Now let us look at the inside of this wonderfully delicious beast!

A Dead Hog Examined

Do you imagine that the repulsiveness of this loathsome creature is only on the outside? That within everything is pure and wholesome? Vain delusion! Sickening, disgusting, as is the exterior, it is, in comparison with what it covers, a fair cloak, hiding a mass of disease and rottenness which grows more superlatively filthy as we penetrate deeper and deeper beneath the skin.

What Is Lard?

Just under the foul and putrid skin we find a mass of fat from two to six inches in thickness, covering a large portion of the body. Now what is this? Lard, says one; animal oil; an excellent thing for consumptives; a very necessary kind of food in cold weather. Lard, animal oil, very truly; and, we will add a synonym for disease, scrofula, torpid liver. Where did all that fat come from, or how happened it to be so heaped up around that poor hog? Surely it is not natural; for fat is only deposited in large quantities for the purpose of keeping the body warm in winter. This fat is much more than is necessary for such a purpose, and is much greater in amount than ever exists upon the animal in a state of nature. It is evidently the result of disease. So gross have been the habits of the animal, so great has been the foulness of its body, that its excretory organs--its liver, lungs, kidneys, skin, and intestines--have been entirely unable to carry away the impurities which the animal has been all its life accumulating. And even the extensive system of sewerage with its constant stream, which we have already described, was insufficient to the task of purging so vile a body of the debris which abounded in every organ and saturated every tissue. Consequently this great flood of disease, which made its way through the veins and arteries into the tissues, and there accumulated as fat! Delectable morsel, a slice of fat pork, isn�t it? Concentrated, consolidated filth!

Then the fatter the hog, the more diseased he is? Certainly. A few years ago, there were on exhibition at the great cattle show in England a couple of hogs which had been stuffed with oil cake until they were the greatest monsters of obesity ever exhibited. Of course they took the first premium; and if a premium had been awarded to the animals which were capable of producing the most disease, it is quite probable that they would have headed the list still.

Lard, then, obtained from the flesh of the hog by heating, is nothing more than extract of a diseased carcass! Who that knows its character would dare to defile himself with this "broth of abominable things?"

Disgusting Developments

Now let us take a little deeper look, prepared to find disease and corruption more abundant the deeper we go. Observe the glands which lie about the neck. Instead of being of their ordinary size, and composed of ordinary gland structure, we find them surrounded by large masses of scrofulous tissue. Perhaps tuberculosis degeneration had already taken place. If so, the soft, cheesy, infectious mass is ready to sow broadcast the seeds of consumption and premature death. For, according to some excellent authorities, tuberculosis disease is capable of communication by means of tubercles. If the animal is of sufficient age, the further process of ulceration will have occurred.

Now take a deeper look still, and examine the lungs of this much-prized animal. If he is more than a few months old, you will be likely to find large numbers of tubercles. If he is much more than a year old, you will be more likely than not to find a portion of the lung completely consolidated. Yet all of this filthy, diseased mass is cooked as a delicious morsel, and served up to satisfy fastidious tastes. If the animal had escaped the butcher�s knife a few years, he would have died of tuberculosis consumption.

But what kind of a liver would you expect such an animal to have? Is not excessive fatness one of the surest evidences of a diseased and inactive liver? �infallible! Then a fat hog must have a dreadfully diseased bile manufactory. Make a cut into its substance. In seventy-five cases out of a hundred you will find it filled with abscesses. In a larger percentage still will be found the same diseased products which seem to infest every organ, every tissue, every structure of the animal. Yet these same rotten, diseased, scrofulous livers are eaten and relished by thousands of people who cannot express their contempt for the Frenchman who eats a horse or the China man who dines upon fricasseed puppy.

Now just glance at the remaining contents of the abdomen. In every part you notice evidences, unmistakable, of scrofula, fatty degeneration, and tuberculosis masses.

Where Scrofula Comes From

The word scrofula is derived from the Latin scrofu, which means a sow. The ancient Romans evidently believed that scrofula originated with the hog, and hence they attached the name of the beast to the disease. Saying that a man has scrofula, then, is equivalent to saying that he has the hog disease. After we have seen that the hog is the very embodiment of scrofulous disease, can any one doubt the accuracy of the conclusion of the Romans who named the disease?

Origin of the Tapeworm

We shall attempt to trace the history of this horrid parasite only so far as concerns its introduction into the human system.

With this end in view, let us glance again at the diseased liver. It will be no uncommon thing if we discover numberless little sacs, or cysts, about the size of a hemp seed. These do not present a very formidable appearance, certainly; but as soon as they are taken into the human stomach, the gastric juice dissolves off the membranous sac, and liberates a minute animal, which had been lurking there for months, perhaps, awaiting this very opportunity. This creature, although very small, is furnished with a head and four suckers, attach themselves firmly to the wall of the intestine, and the parasite begins to grow. In a short time an addition to its body is produced posteriorly, attached like a joint. Soon a duplicate of this appears, and then another, and another, until the body attains a length of several yards. Not infrequently tapeworms measuring thirty to one hundred feet in length are found in the intestines of human beings.

Under some circumstances the eggs of the tapeworm find entrance into the body, when the disease is developed in another form. The embryonic worms consist of a pair of hooklets so shaped that a twisting motion will cause them to penetrate the tissues after the fashion of a corkscrew. Countless numbers of these may be taken into the system, since a single tapeworm has been found to produce more than two million eggs. By the boring motion referred to, which seems to be spontaneous in the young worm, the parasites penetrate into every part of the body. Penetrating the walls of the blood vessels, they are swept along in the life-current, thus finding their way even to the most delicate structures of the human system. They have been found in all the organs of the body, even the brain and the delicate organs of vision not escaping the depredations of this destructive parasite.

When this lively migrating germ gets fully settled in the tissues, it becomes enveloped in a little cell, and remains quiet until taken into the stomach of some other animal, when it is liberated, and speedily develops into a full-grown tapeworm, as already described. But although quiet, the imprisoned parasite is by no means harmless. The cysts formed often attain such a size as to endanger life. When developed in the eye, they occasion blindness; in the lungs or other organs, they interfere with the proper functions of the organs; in the liver, which is the frequent rendezvous of these destructive creatures, a most serious and fatal disease known as hydatids is occasioned by the extraordinary development of the cysts, which are originally not larger than a pea, but by excessive growth assume enormous proportions. The same disease may occur in any other part of the body in which the germs undergo development.

The germs of these dreadful animals are found not only in the liver, but in other organs as well. Pork containing them is said to be "measly." Sometimes the condition is discovered; but that such is not always the case is evidenced by the fact that tapeworm is every year becoming more frequent. It has long been common in Germany. In Iceland it has become extremely common. In Abyssinia the occurrence of the worm has become so frequent, owing to the bad dietetic habits of the people, that it has been said that every Abyssinian has a tapeworm. In this country the parasite is most common among butchers and cooks.

Some time since, we received from a friend in the South a specimen of pork which was so densely peopled with the germs of this dreadful parasite that every cubic inch of flesh contained more than a score of them. The writer has in his microscopical cabinet specimens of the embryonic worms taken from hydatid tumors of the liver of a patient who died of the disease in Bellevue Hospital, New York.

The poor victim who is forced to entertain this unwelcome guest suffers untold agonies, and finally dies, if he cannot succeed in dislodging the parasite.

The Terrible Trichina

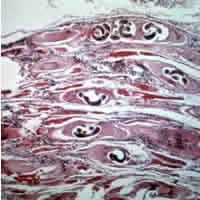

Now, my friend, assist your eyesight by a good microscope, and you will be convinced that you have only just caught a glimpse of the enormous filthiness, the inherent badness, and the intrinsic ugliness of this loathsome animal. Take a thin slice of lean flesh; place it upon the stage of your microscope, adjust the eyepiece, and look. You will see displayed before your eyes hundreds of voracious little animals, each coiled up in its little cell, waiting for an opportunity to escape from its prison walls and begin its destined work of devastation.

An eminent gentleman in Louisville has made very extensive researches upon the subject, and asserts that in at least one hog out of every ten these creatures may be found. A committee appointed by the Chicago Academy of Medicine to investigate this subject reported that they found in their examinations at the various packing-houses in the city, one hog in fifty infested with trichina. Other investigations have shown a still greater frequency of the disease.

A few years ago I obtained a small portion of the flesh of a person who had died from trichina poisoning. Upon subjecting it to a careful microscopical examination with a good instrument, I discovered multitudes of little worms. Each individual presented the appearance shown in the accompanying accurate engraving. The animal is there seen enclosed in a little cyst, or sac, which is dissolved by the gastric juice when taken into the stomach. The parasite, being thus set at liberty, immediately penetrates the thin muscular walls of the stomach, and gradually works its way through the whole muscular system. It possesses the power of propagating its species with wonderful rapidity; and a person once infected is almost certain to die a lingering death of excruciating agony.

In Helmstadt, Prussia, one hundred and three persons were poisoned in this way, and twenty of them died within a month.

It is doubtless not known how many deaths are really due to this cause; for many persons die of strange, unknown diseases, which baffle the doctors� skill both as to cure and diagnosis. Trichinosis very much resembles various other diseases in some of its stages, and is likely to be attributed to other than its true cause. It is thought by prominent medical men that hundreds of people die of the disease without suspecting its true nature.

Pork Unclean

Have we not seen that a hog is nothing better than an animated mass of physical defilement? Few who have seen the animal will dispute that his filthiness is a most patent fact. How wise and sanitary, then, was the command of God to the ancient Jews: "It is unclean unto you. Ye shall not eat of their flesh nor touch their dead carcass."

Although it may not be said that this law still exists, and is binding as a moral obligation, it is quite plain that the physical basis upon which the law is founded is as good today as at any previous period. Could it be proved that the hog had kept pace with advancing civilization, and had improved his habits, we might possibly feel more tolerance for him; but he is evidently just as unclean as ever, and just as unfit for food.

Adam Clarke, when once requested to give thanks at a repast of which pork constituted a conspicuous part, used the following words: "Lord, bless this bread, these vegetables, and this fruit; and if thou canst bless under the gospel what thou didst curse under the law, bless this swine�s flesh."

The Mohammedans, as well as the Jews, abstain entirely from the use of pork. Such is also the case with some of the other tribes of Asia and Africa.

Evil Effects of Pork-Eating

At the head of the list we place scrofula. How almost universally it abounds. How few are entirely untainted by it. How do chronic sore eyes, glandular enlargements, obstinate ulcers, disfigured countenances, unsightly eruptions, including the long list of skin diseases, all proclaim the defilement of the blood with this vile humor. So, too, do the vast army of dwarfed, strumose, precocious children tell the same story.

Erysipelas, too, a dreadful scourge, owes more to pork than to any other predisposing cause.

Leprosy, that terrible disease, so common in Eastern countries, and now beginning to show itself upon our own shores, is thought by many to be largely attributable to pork-eating.

"Biliousness," a name which covers nearly every bad condition for which no appropriate name can be found, is notoriously the result of pork-eating. This is the main reason why so many people complain of biliousness in the spring, after gorging themselves with fat pork all winter. The liver is overworked in attempting to remove from the system such a mass of impurity as is received in the eating of pork. It consequently becomes clogged, congested, torpid. Then follow all the ills consequent upon the irritating effects of the accumulation of biliary matters in the blood. The skin becomes tawny and jaundiced. The kidneys are overworked. Perhaps fever results. A partial clearing out then occurs, which enables the individual to pass along for a time again until some epidemic or contagious disease claims him as its lawful victim.

Consumption is another disease which is not easily separable from pork-eating. In fact, scrofula is its great predisposing cause. The narrow chests, projecting shoulders, thin features, and lank limbs of so many young boys and girls are evidence of a consumptive tendency, of which a scrofulous diathesis is the predisposing cause.

Dispepsia, that malady of many forms, frequently results from the use of pork, especially when fat and salted or smoked pork, one of the most indigestible of foods, is used. Pork requires between five and six hours for its digestion, while wholesome food will digest in half that time. This is the reason for the notion that salt pork is an excellent thing to "stick by the rib."

Tapeworm, we have already mentioned as the result of eating measly pork. It is a very difficult disease to cure, and often baffles the best medical skill for many years. Few ever detect the cysts in the flesh of the hog unless their attention has been directed to the matter.

Trichinae produce in man an incurable disease. No remedy can stay the ravages of the parasite. All pork-eaters are in constant danger; for the worm is too small to be seen without the aid of the microscope. However, this disease is not nearly so formidable as the others named; for it is not so common, neither does it entail any weight of suffering upon posterity.

Apologies For Pork-Eating Examined

On every hand we are met by all sorts of excuses for continuing to make swine�s flesh an article of diet in spite of the striking evidences of its dangerous character. Let us examine a few of the most common of these apologies, and test their value.

Pork is Necessary as a Heat-forming Food in Winter � Are there not plenty of more healthful animals than hogs to supply all the animal fat necessary? Certainly there are; and, better still, we have the various grains and farinaceaous vegetables, which are abundantly sufficient to furnish all the heat required by man in any latitude.

Our Fathers and Grandfathers Ate Pork, and yet Lived to very Old Age � Ah! yes, my good friend, and you are suffering the penalty of their transgressions. You may not be aware of it yet; but more than likely your old age will not be so free from ills as was theirs. And quite as probably you may even now see in your children the results of your own, as well as your fathers, disregard of the dictates of sound sense in feasting upon the hog. Their frequent sore eyes, sore mouths, tetter, crysipelas, and other eruptions, are all evidences of the scrofula which they have inherited.

Neither can you urge the plea, "Pork does not hurt me." No man ever became a drunkard who did not make the same excuse for liquor. You may not feel it now; but the future will expose your delusion.

The Hog is Cleanly if You Give Him a Chance to Be so � It is surprising to us that any one who knows anything of the real nature of a hog can make such an assertion. Who has not seen hogs wallowing in the foulest mire right in the middle of a green, fragrant clover pasture? The dirty creature will turn away from the nicest bed of straw to revel in a stagnant, seething mud hole. If one of his companions dies in the lot or pen, he will wait until putrefaction occurs, and then greedily devour the stinking carcass. The filthy brute will even devour his own excrement, and that when not unusually pressed by hunger.

The hog is by nature a scavenger, and is especially adapted for that purpose. Let him pursue his natural hunger.

Sufficient Heat Will Kill the Trichinae and Incipient Tapeworms � Surely, dead worms cannot kill any one; but it must be delightful for the pork-eater to contemplate his ham or sausage with the reflection that he is partaking of a diet of worms. The Frenchman sometimes eats earthworms; the African relishes lizards; and one philosopher so far overcame his natural prejudices as to eat spiders. "How disgusting!" you say, and you shut your eyes and swallow a million monsters at a meal, because they are cooked and so cannot bite. The louse-eating Patagonian cannot equal that. But it should be remembered that in order that the parasite should be killed, every part of the meat must be subjected to a heat of at least 2l2� which is quite difficult to do, and is seldom accomplished. A whole family was poisoned by eating pork-chops, which were well cooked upon the outside.

What Shall We Do With the Hog?

Stop raising him. Turn him loose. He will soon find his place, like the five thousand which ran down into the sea in the days of Christ. If he must be raised, use him for illuminating our halls and houses. Lubricate our car and wagon with his abundant fat. Do anything with him but eat him. It would be dangerous to adopt the principle that we must devour everything which is in the way, or which cannot be otherwise utilized. Adam Clarke thought of one appropriate use to make of the hog. He said that if he was going to make an offering to the devil, he would employ a hog stuffed with tobacco.

Reader, what will you do? Can you continue to use as food such an abominable article as pork, and in so doing run so many risks as you must do? And if you decide that the animal is unfit to claim a place upon your own table, can you conscientiously raise and sell him to your neighbors� injury?

Cases of Trichina Poisoning

The reported cases of death from this terrible cause have become so frequent that we are no longer startled by them. Ten years ago the description of the death of a person literally infested with worms, and tortured to death by their inroads upon the system, would have excited feelings of the deepest horror; but these accounts have now become so common that little interest is shown in them, and death from this cause is one of the regular causes of additions to the mortuary list. Nevertheless, the disease is divested of none of its real horrors by its common occurrence. No one is safe; any one who uses swine�s flesh as food in any form is liable to the disease. Salting, smoking, and the other ordinary means of curing pork do not destroy the parasite.

A few years ago, Dr. Germer, health officer of Erie, Pa., was sent for in haste to see a patient who was supposed to be suffering from the cholera. He hastened to the bedside, and found a whole family sick with the symptoms much resembling those of cholera, though the season was then midwinter. Suspecting the possible cause, he secured a specimen from the pork barrel, and hastened to his office. Upon making a careful microscopic examination, he found myriads of the loathsome parasites in every part of the flesh examined. The writer prepared numerous microscopic specimens of the worm in various aspects from a portion of the infected meat kindly furnished by the doctor. These have been shown to hundreds of persons who were skeptical respecting the existence of such a pest.

In this case the hog had been fattened on the premises, having been purchased when quite young by the owner, a German, from a drove of hogs which passed through the city. It was known that, previous to the purchase of the hog, two of the drove had died on the road, and had been devoured by their scavenger companions. No doubt the deaths were the result of trichinosis; and by devouring the victims the whole herd became infected. It would be difficult to estimate what an amount of suffering and death was entailed by the consumption of this great herd of trichinous hogs. Several members of the German family died, together with several of the neighbors. Those who survived the acute stages of the disease escaped only to linger out a painful existence in the chronic and incurable state of the malady.

Some three years later the writer received a specimen of pork from a gentleman in Wisconsin who requested an examination of the same, stating that he procured it from the pork barrel of a neighbor whose family were suffering from a disease which the doctors called cholera infantum. Several of the children had died, and other members of the family were still dangerously ill. The pork had been suspected and examined, but no trichinae were found by the observers, though several physicians had inspected it. Upon making a careful microscopical inspection of the specimen, it was found to be alive with young trichinae.

http://www.giveshare.org/Health/porkeatdanger.html

Trichinosis

| Trichinosis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Trichinella spiralis larva displayed in a typical coil shape. | |

| ICD-10 | B75 |

| ICD-9 | 124 |

| DiseasesDB | 13326 |

| MeSH | D014235 |

Trichinosis, also called trichinellosis, or trichiniasis, is a parasitic disease caused by eating raw or undercooked pork or wild game infected with the larvae of a species of roundworm Trichinella spiralis, commonly called the trichina worm. There are eight Trichinella species; five are encapsulated and three are not.[1] Only three Trichinella species are known to cause trichinosis: T. spiralis, T. nativa, and T. britovi.[1] The few cases in the United States are mostly the result of eating undercooked game, bear meat, or home-reared pigs. It is common in developing countries where meat fed to pigs is raw or undercooked, but many cases also come from developed countries in Europe and North America, where raw or undercooked pork and wild game may be consumed as delicacies.[2]

Contents[hide] |

Agent and taxonomy

Agent

The disease-causing agents include the eight species of Trichinella, but T. spiralis is the most important to humans due to its worldwide distribution and high pathogenicity.[3]

Species and characteristics

- T. spiralis is most adapted to swine, most pathogenic in humans and is cosmopolitan in distribution.

- T. britovi is the second most common species to infect humans; it is distributed throughout Europe, Asia, and northern and western Africa usually in wild boar and domesticated pigs.

- T. nativa, which has a high resistance to freezing, is found in the Arctic and subarctic regions; reservoir hosts include polar bears, arctic foxes, walruses and other wild game.

- T. pseudospiralis infects birds and mammals, and has demonstrated infection in humans;[4] it is a nonencapsulated species.

- T. papuae infects both mammals and reptiles, including crocodiles, humans, and pigs; this species, found in Papua New Guinea and Thailand, is also nonencapsulated.

- T. nelsoni, found in eastern Africa, has been documented to cause a few human cases.

- T. murrelli also infects humans, especially from black bear meat; it is distributed among wild carnivores in North America.

- T. zimbabwensis can infect mammals and possibly humans; this nonencapsulated species was detected in reptiles of Africa.

Taxonomy

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Nematoda

- Class: Adenophorea

- Order: Trichurida

- Family: Trichinellidae

- Genus: Trichinella

History of the discovery

Discovery of the parasite

The circumstances surrounding the first observation and identification of Trichinella spiralis are controversial due to a lack of medical records. In 1835, James Paget, a first-year medical student, first observed the larval form of T. spiralis while witnessing an autopsy at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. Paget took special interest in the presentation of muscle with white flecks, described as a “sandy diaphragm”.

Although Paget is most likely the first person to have noticed and recorded these findings, the parasite was named and published in a report by his professor, Richard Owen, who is now credited for the discovery of the T. spiralis larval form.[5]

Discovery of the life cycle

A series of experiments conducted between 1850 and 1870 by the German researchers Rudolf Virchow, Rudolf Leuckart and Friedrich Albert von Zenker, which involved feeding infected meat to a dog and performing the subsequent necropsy, led to the discovery of the life cycle of Trichinella. Through these experiments, Virchow was able to describe the development and infectivity of T. spiralis.[6]

Signs and symptoms

The great majority of trichinosis infections have either minor or no symptoms and no complications. [1] There are two main phases for the infection: enteral (affecting the intestines) and parenteral (outside the intestines). The symptoms vary depending on the phase, species of Trichinella, amount of encysted larvae ingested, age, gender, and host immunity.[7]

[edit] Enteral phase

A large burden of adult worms in the intestines promote symptoms such as nausea, heartburn, dyspepsia, and diarrhea from two to seven days after infection, while small worm burdens generally are asymptomatic. Eosinophilia presents early and increases rapidly.[8]

Parenteral phase

The severity of symptoms caused by larval migration from the intestines depends on the number of larvae produced. As the larvae migrate through tissue and vessels, the body's inflammatory response results in edema, muscle pain, fever, and weakness. A classic sign of trichinosis is periorbital edema, swelling around the eyes, which may be caused by vasculitis. Splinter hemorrhage in the nails is also a common symptom.[9]

The most dangerous case is worms entering the central nervous system (CNS). They cannot survive there, but they may cause enough damage to produce serious neurological deficits (such as ataxia or respiratory paralysis), and even death. The CNS is compromised by trichinosis in 10-24% of reported cases of a rare form of stroke.[10] Trichinosis can be fatal depending on the severity of the infection; death can occur 4–6 weeks after the infection,[11] and is usually caused by myocarditis, encephalitis, or pneumonia.[3]

Life cycle

The typical life cycle for T. spiralis involves humans, pigs, and rodents. Pigs become infected when they eat infectious cysts in raw meat, often pork or rats (sylvatic cycle). Humans become infected when they eat raw or undercooked infected pork (domestic cycle). After humans ingest the cysts from infected undercooked meat, pepsin and hydrochloric acid help free the larvae in the cysts in the stomach.[7] The larvae then migrate to the small intestine, where they molt four times before becoming adults.[7]

Thirty to 34 hours after the cysts were originally ingested, the adults mate, and within five days produce larvae.[7] The worms can only reproduce for a limited time because the immune system will eventually expel them from the small intestine.[7] The larvae then use their piercing mouthpart, called the “stylet”, to pass through the intestinal mucosa and enter the lymphatic vessels, and then enter the bloodstream.[5] The larvae travel by capillaries to various organs, such as the retina, myocardium, or lymph nodes; however, only larvae that migrate to skeletal muscle cells survive and encyst.[11] The larval host cell becomes a nurse cell in which the larvae will be encapsulated. The development of a capillary network around the nurse cell completes encystation of the larvae.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of trichinosis is confirmed by a combination of exposure history, clinical diagnosis, and laboratory testing.

Exposure history

An epidemiological investigation can be done to determine a patient's exposure to raw infected meat. Often, an infection arises from home-preparation of contaminated meat, in which case microscopy can be used to determine the infection. However, exposure does not have to be directly from an infected animal. Other exposure includes the consumption of products from a laboratory-confirmed infected animal or by sharing a common exposure as a laboratory-confirmed infected human.[11]

Clinical diagnosis

Clinical presentation of the common trichinosis symptoms may also suggest infection. These symptoms include circumorbital edema, splinter hemorrhage, nonspecific gastroenteritis, and muscle pain.[11] The case definition for trichinosis at the European Center for Disease Control states "at least three of the following six: fever, muscle soreness and pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, facial edema, eosinophilia, and subconjuctival, subungual, and retinal hemorrhages." [11]

Laboratory testing

Serological tests and microscopy can be used to confirm a diagnosis of trichinosis. Serological tests include a blood test for eosinophilia, increased levels of creatine phosphokinase, IgG, and antibodies against newly hatched larvae. Immunoassays, such as ELISA, can also be used.[11]

Treatment and vaccines

As is desirable with most diseases, early treatment is better and decreases the risk of developing disease. If larvae do encyst in skeletal muscle cells, they can remain infectious for months to years.[11]

Primary treatment

Early administration of anthelmintics, such as mebendazole or albendazole, decreases the likelihood of larval encystation, particularly if given within three days of infection [9] Unfortunately, most cases are diagnosed after this time.[11]

Mebendazole (200–400 mg three times a day for three days) or albendazole (400 mg twice a day for 8–14 days) are given to treat trichinosis.[12] These drugs prevent newly hatched larvae from developing, but should not be given to pregnant women or children under two years of age.[7]

Secondary treatment

After infection, steroids, such as prednisone and pyrantel, may be used to relieve muscle pain associated with larval migration.

Vaccine research

There are currently no vaccines for trichinosis, although experimental mice studies have suggested a possibility. In one study, microwaved Trichinella larvae were used to immunize mice which were subsequently infected. Depending on dosage and frequency of immunization, results ranged from a decreased larval count to complete protection from trichinosis.[13]

Another study, Dea-Ayuela et al. (2006) used extracts and excretory-secretory products from first stage larvae to produce an oral vaccine.[14] To prevent the gastric acids from dissolving the antigens before reaching the small intestine, scientists encapsulated the antigens in a microcapsule made of copolymers. This vaccine significantly increased CD4+ cells and increased antigen-specific serum IgGq and IgA, resulting in a statistically significant reduction in the average number of adult worms in the small intestine of mice. The significance of this approach is that if the white blood cells in the small intestine have been exposed to Trichinella antigens (through vaccination) then, when an individual gets infected, the immune system will respond to expel the worms from the small intestine fast enough to prevent the female worms from releasing their larvae. Yuan Gu et al. (2008) tested a DNA vaccine on mice which “induced a muscle larvae burden reduction in BALB/c mice by 29% in response to T. spiralis infection”.[15] Researchers trying to develop a vaccine for Trichinella have tried to using either “larval extracts, excretory-secretory antigen, DNA vaccine, or recombinant antigen protein.” [15]

Epidemiology as early as 1835, trichinosis was known to have been caused by a parasite, but the mechanism of infection was unclear at the time. A decade later, American scientist Joseph Leidy pinpointed undercooked meat as the primary vector for the parasite, and it was not until two decades afterwards that this hypothesis was fully accepted by the scientific community.[2]

About 11 million individuals are infected with Trichinella; Trichinella spiralis is the species responsible for most of these infections.[16] Infection was once very common, but is now rare in the developed world. The incidence of trichinosis in the U.S. has decreased dramatically in the past century. From 1997 to 2001, an annual average of 12 cases per year were reported in the United States. The number of cases has decreased because of legislation prohibiting the feeding of raw meat garbage to hogs, increased commercial and home freezing of pork, and the public awareness of the danger of eating raw or undercooked pork products.[17]

In the developing world, most infections are associated with undercooked pork. For example, in Thailand, between 200 and 600 cases are reported annually around the Thai New Year. This is mostly attributable to a particular delicacy, larb, which calls for undercooked pork as part of the recipe. In parts of Eastern Europe, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports some swine herds have trichinosis infection rates above 50%, and there are correspondingly large numbers of human infections. [3]

Reemergence

The disappearance of the pathogen from domestic pigs has led to a relaxation of legislation and control efforts by veterinary public health systems. It has since been thought of as a reemerging zoonosis supplemented by the increased distribution of meat products, political changes, a changing climate, and increasing sylvatic transmission.[18]

It is also important to keep in mind major socio-political changes can produce conditions that favor the resurgence of Trichinella infections in swine and, consequently, humans. For instance, “the overthrow of the social and political structures in the 1990s” in Romania led to an increase in the incidence rate of trichinosis.[19] There is also a high incidence of trichinosis among refugees from Southeast Asia.[11] China reports approximately 10,000 cases every year, and is therefore the country with the highest numbers of cases.[11] In China, between 1964-1998 over 20,000 people were infected with Trichinosis and over 200 people died.[20]

The kashrut and halal dietary laws of Judaism and Islam prohibit eating pork. In the 19th century, when the association between trichinosis and undercooked pork was first established, it was suggested this association was the reason for the prohibition, reminiscent of the earlier opinion of the medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides that food forbidden by Jewish law was "unwholesome". This theory was controversial and eventually fell out of favor.[21]

International Commission on Trichinellosis

The International Commission on Trichinellosis (ICT) was created in 1958 in Budapest and is aiming to exchange information on the biology, the physiopathology, the epidemiology, the immunology, and the clinical aspects of trichinellosis in humans and animals. Prevention is a primary goal. Since the creation of the ICT, its members (more than 110 from 46 countries) have regularly gathered and worked together during meetings held every four years : the International Conference on Trichinellosis.

Prevention

Legislation

Laws and rules required of food producers may improve food safety for consumers, such as the rules established by the European Commission for inspections, rodent control, and improved hygiene.[11] Similar protocol exists in the United States in the USDA guidelines for establishment responsibilities in inspecting pork.[22]

Education and training

Public education about the dangers of consuming raw and undercooked meat, especially pork, may reduce infection rates. Hunters are also an at-risk population due to their contact and consumption of wild game, including bear. As such, many states, such as New York, require the completion of a course in such matters before a hunting license can be obtained.[23]

Food preparation

Larvae may be killed by the heating or irradiation of raw meat. Freezing is only usually effective for T. spiralis, since other species, such as T. nativa, are freeze resistant and can survive long-term freezing.[11]

- All meat (including pork) can be safely prepared by cooking to an internal temperature of 165 °F (74 °C) or more for 15 seconds or more.

- Wild game: Wild game meat must be cooked thoroughly (see meat preparation above) Freezing wild game does not kill all trichinosis larval worms. This is because the worm species that typically infests wild game can resist freezing.

- Pork: Freezing cuts of pork less than 6 inches thick for 20 days at 5 °F (−15 °C) or three days at −4 °F (−20 °C) kills T. spiralis larval worms but will not kill other trichinosis larval worm species such as T. nativa if they have infested your pork food supply (which is unlikely).

Pork can be safely cooked to a slightly lower temperature provided the internal meat temperature is at least as hot for least as long as listed in the USDA table below.[24] Nonetheless, it is prudent to allow a margin of error for variation in internal temperature within a particular cut of pork, which may have bones that affect temperature uniformity. In addition, your thermometer has measurement error that must be considered. Cook pork for significantly longer and at a higher uniform internal temperature than listed here to be safe.

| Internal Temperature | Internal Temperature | Minimum Time |

|---|---|---|

| (°F) | (°C) | (minutes) |

| 120 | 49 | 1260 |

| 122 | 50.0 | 570 |

| 124 | 51.1 | 270 |

| 126 | 52.2 | 120 |

| 128 | 53.4 | 60 |

| 130 | 54.5 | 30 |

| 132 | 55.6 | 15 |

| 134 | 56.7 | 6 |

| 136 | 57.8 | 3 |

| 138 | 58.9 | 2 |

| 140 | 60.0 | 1 |

| 142 | 61.1 | 1 |

| 144 | 62.2 | Instant |

Unsafe and unreliable methods of cooking meat include the use of microwave ovens, curing, drying, and smoking, as these methods are difficult to standardize and control.[11]

Hygienic pig farming

- Cooking all meat fed to pigs or other wild animals

- Keeping pigs in clean pens with floors that can be washed (such as concrete)

- Not allowing hogs to eat uncooked carcasses of other animals, including rats, which may be infected with Trichinella

- Cleaning meat grinders thoroughly when preparing ground meats

- Control and destruction of meat containing trichinae, e.g., removal and proper disposal of porcine diaphragms prior to public sale of meat

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention makes the following recommendation: "Curing (salting), drying, smoking, or microwaving meat does not consistently kill infective worms."[26] However, under controlled commercial food processing conditions, some of these methods are considered effective by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).[27]

The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is responsible for the regulations concerning the importation of swine from foreign countries. The Foreign Origin Meat and Meat Products, Swine section covers swine meat (cooked, cured and dried, and fresh). APHIS developed the National Trichinae Certification Program; this is a voluntary “preharvest” program for U.S. swine producers “that will provide documentation of swine management practices” to reduce the incidence of Trichinella in swine.[28] The CDC reports 0.013% of U.S. swine is infected with Trichinella.[28https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trichinosis

No comments:

Post a Comment